French count stood up an important man in Lewes

Back in the fall of 1779, the squealing infant called the United States of America was struggling to throw off the stubborn clutches of Great Britain. General George Washington had rallied his troops from his camp west of Philadelphia to repel British advances in the northeast.

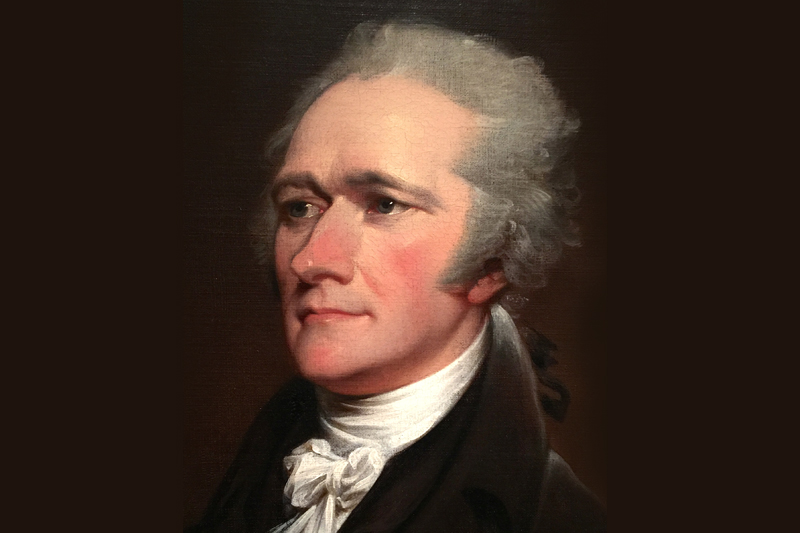

Alexander Hamilton, hero of the current hip-hop Broadway hit called “Hamilton,” placed himself in the thick of the action. As a lieutenant colonel in the revolutionary forces, he gained Washington’s confidence and served as his chief aide during - and of course after - these pivotal times in our nation’s history. Washington, in the midst of keeping his Army together and focused, also had to play offense and defense.

In many respects, Hamilton was his quarterback. Washington made his plans and issued orders. Hamilton’s job was to pass those orders to the right people and make sure everyone worked on the same page and executed.

But while Washington was successful in staving off British advances in the northern states, the royal navy and its associated troops laid siege to Savannah in Georgia. There, the British hoped to establish a beachhead where they could settle in and begin advancing northward to reclaim their sovereignty over the rebellious states.

Here comes the count

The French and English, rivals for centuries and always battling on land or sea for one reason or another, were nurturing their usual animosity during this time. Aided by Benjamin Franklin’s persuasive ways, the French agreed to join the states in their battle against the British. The French king sent an acclaimed naval officer named Charles Hector, Comte D’Estaing [otherwise known as Count D’Estaing], to the assistance of Washington and his American rebels.

D’Estaing commanded a sizeable fleet of warships and thousands of troops gathered from French colonies in the Caribbean. Then he gambled against the threat of hurricanes that thrive in that part of the world and headed northward in the open seas. With the sketchy-at-best communication that drove military strategy in those days prior to telecommunication, D’Estaing heeded Washington’s call to break the British stranglehold on Savannah.

I know all of this because Lewes Historical Society Executive Director Mike DiPaolo pointed me to sources on the internet where correspondence and information from this time is available.

Once the count reached Savannah, the good fortune that had allowed his fleet to escape hurricanes quickly faded. His assault on the Brits started on Sept. 16, 1779 and ended a month later on Oct. 18.

“D’Estaing suffered a crushing defeat at Savannah,” said DiPaolo. He had to retreat, leaving the city under British control.

Here is where this story shifted, scantily, to Lewes. DiPaolo has copies of correspondence between Washington and Hamilton in which the general dispatches his aide to Lewes to rendezvous with D’Estaing’s fleet. DiPaolo said the correspondence doesn’t explain what Washington wanted Hamilton to discuss with the count. “Maybe he wanted to find out how things had gone in Savannah,” said DiPaolo, “but the letters provide no context.”

Hamilton sailed out of Philadelphia to reach Lewes for his hoped-for rendezvous. At the same time, D’Estaing’s fleet was making its way northward. Washington at this time was also planning an attack on British forces in Virginia, and D’Estaing could be helpful there.

A pivotal location between the northern and southern states, Lewes was an important communication center. Henry Fisher lived near the fort that occupied the high ground where the Dutch originally settled in 1631.

From there, he monitored shipping activity along the coast, and coming in and out of Delaware Bay, and sent a steady stream of communications to Philadelphia, and on to Washington to bolster his intelligence. He corresponded frequently with Hamilton as well. Hamilton may have stayed with Fisher in his home, which still stands and is known as Fisher’s Paradise.

“Lewes had two forts at that time, a field hospital, and other military facilities,” said DiPaolo. They all occupied ground near where the historical complex is now. There were also taverns, inns, residences and other commercial establishments in the town, which by this time was more than 100 years old.

No record rendezvous occurred

The story could get exciting at this point, but it doesn’t. Hamilton made his way to Lewes and waited a few days hoping to rendezvous with the count. “But apparently it never happened,” said DiPaolo. Hamilton ended up leaving Lewes for Great Egg Harbor in New Jersey hoping to meet up with D’Estaing there.

But in the meantime, Alexander Hamilton - one of our nation’s founding fathers, creator of our banking system and a strong proponent and architect of our centralized federal government - strode the streets of Lewes. Maybe he enjoyed the typically lovely fall weather that comes at that time of the year, but more than likely he just waited with that uncomfortable nervousness that accompanies uncertainty.

D’Estaing and his forces eventually helped Washington and his forces to prevail in the new United States. He returned to France where, for all his service to the crown, he was greeted by a trip up the gallows during the throes of that nation’s own revolution against its royalty.

DiPaolo said the Hamilton visit to Lewes will be a small part of a display in the new Lewes History Museum being crafted now in the Margaret H. Rollins Community Center. Lewes’s role in the American Revolution will be the focus of that display in the former Lewes Public Library.

It’s likely that Benjamin Franklin also visited Lewes. “He sailed to and from Philadelphia so often that it’s hard to believe he didn’t stop here once or twice,” said DiPaolo.

But unlike the written correspondence from George Washington that dispatched Hamilton to Lewes, and correspondence back to Washington from Hamilton while he was in Lewes, there is no concrete evidence for Franklin’s presence in the town.

For now at least, Hamilton may hold claim to being the most important historical figure to ever visit this part of Delaware. “It’s a footnote,” said DiPaolo. “But a fun footnote.”