Warren ‘Yankee’ Miller’s noteworthy life of baseball

For a few years, the Lewes Base Ball Club had a former player who took the field for both the New York Yankees and the Boston Red Sox organizations. No, it wasn’t George Herman Ruth or Wade Boggs.

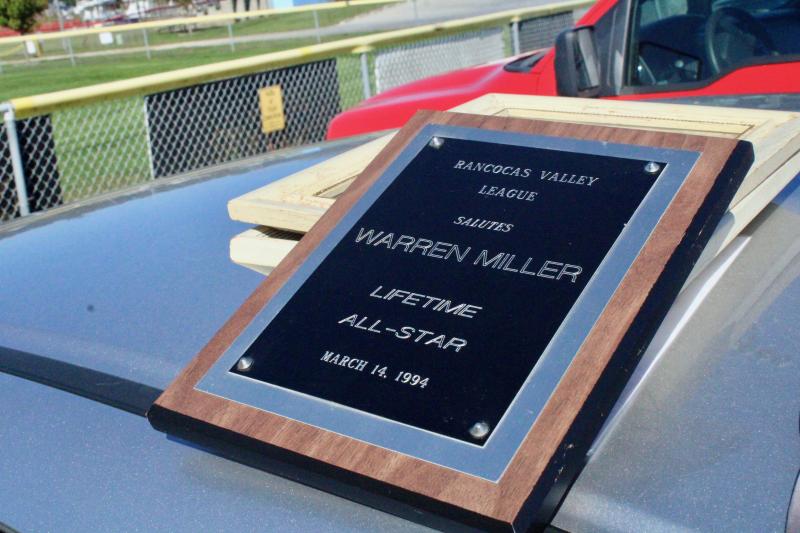

Warren “Yankee” Miller was the only professional baseball player to emerge from now-defunct Merchantville High School in Merchantville, N.J. Born Aug. 28, 1944, in Camden, Miller went on to star in the Rancoca Valley League before his skills were noticed by the Bronx Bombers.

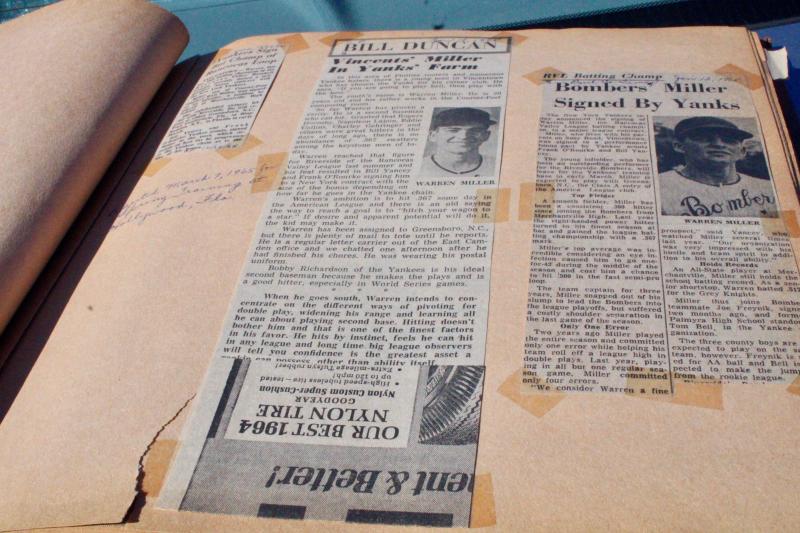

“I had been playing with the Riverside Bombers in the Rancocas Valley League and won a batting championship there in 1964. I hit .367 and a guy by the name of Bill Yancey noticed me,” Miller said.

Yancey was a standout shortstop in the Negro League with a high baseball IQ. He’s also a member of the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

“He gave me the opportunity to go to Yankee Stadium for a tryout. I had a good day there. I went 2-for-4, and I can remember one [at bat] in particular. There was a guy on second and the pitcher – he’s trying to make the ball club as well – threw me a curveball, and I stayed right with it and roped it over the second baseman’s head to right center,” Miller said.

The Yankees signed Miller at the age of 20 in 1965 to play for their rookie ball affiliate, the Johnson City Yankees of the Appalachian League. Signed as a second baseman, Miller caught the eye of Yankees coach Cloyd Boyer.

“Boyer took me under his wing and taught me the inner game of baseball. They moved me from second base over to shortstop because I had a good arm,” Miller said.

Boyer played a big role in Miller’s development as a professional fielder.

“Boyer would go out there and hit ground balls to me with the fungo bat,” Miller said.

Miller got a Coke if he got 10 in a row. He would get to No. 6 and a simple bounce inches away would force them to restart.

“He’d hit hundreds of balls to me – that’s what a coach does. He taught me how to be a shortstop, but he also taught me positioning, where to be, how to take a throw from the outfielder,” Miller said.

Boyer told him how to field a ball on the bounce or deliver a throw to the right spot at first for a stretch or any other plate for a tag.

Collecting 119 plate appearances in 27 games, Miller ended his season with more walks (22) than strikeouts (10) and complemented his .295 batting average with an outstanding .427 on-base percentage. Miller said instruction from Wally Moses, Boyer and Johnson City manager Hank Baur taught him how to be patient and learn where the strike zone is. Miller took their advice and combined it with hours of batting practice to improve his hitting.

His numbers for the year could have been better. After dislocating his left shoulder on a delayed steal, Miller’s time with the Yankees was on life support.

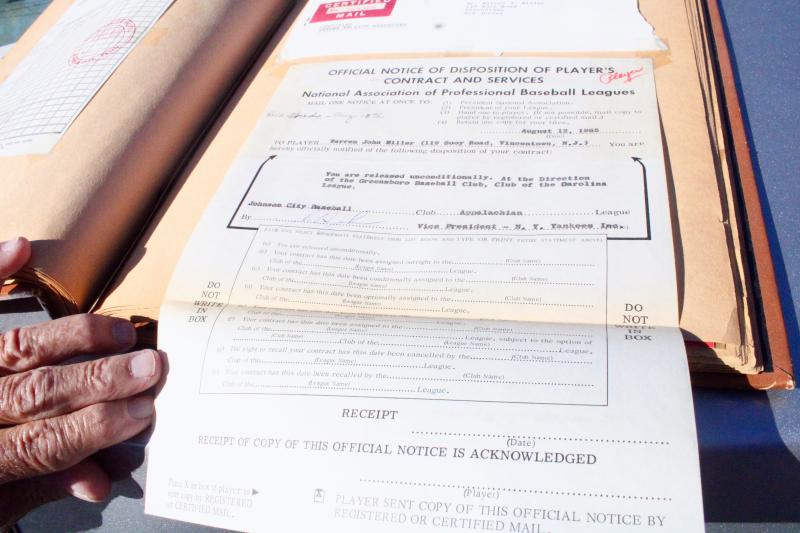

“I tried to come back a little too soon, because that’s my nature, and I couldn’t break a pane of glass with my bat. I dropped down from .338 to .295, and Aug. 12, 1966, they sent me home. That was one of the darkest days of my life,” Miller said.

Following an emotional train ride, Miller had an operation to repair his shoulder. A screw was installed to hold in place a bone from his hip on his shoulder. He then got to work being his own agent and contacted several teams he knew saw him play.

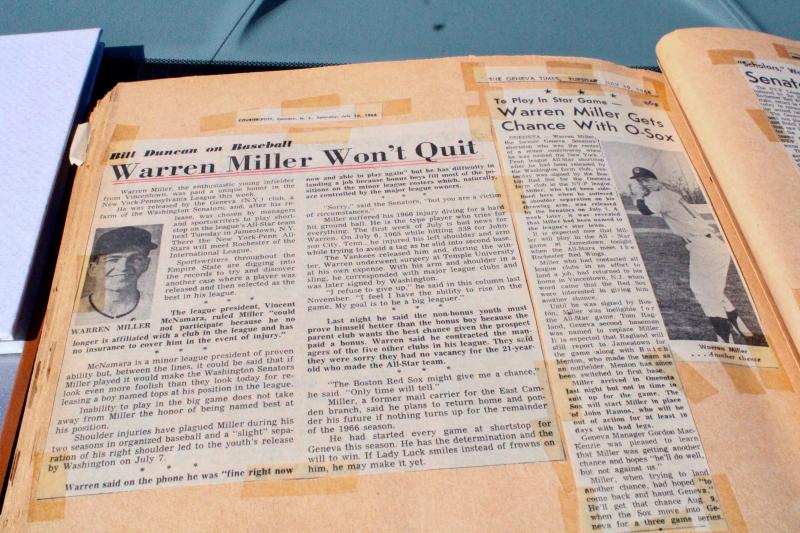

The Washington Senators, the Rangers version, acquired Miller prior to the 1966 season and assigned him to their single-A affiliate in the New York Pennsylvania League, the Geneva Senators.

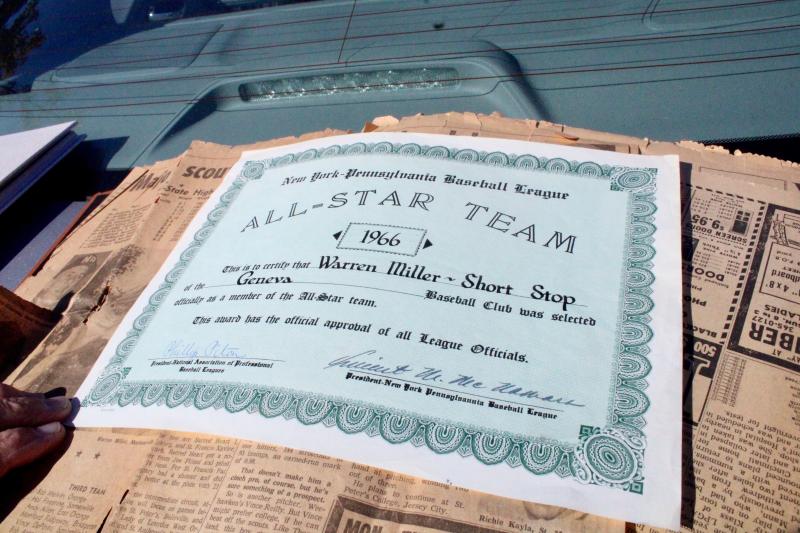

As the Senators struggled, Miller played so well that he was selected to the league’s all-star team as a shortstop. Unfortunately, by the time the game was set to be played, Miller had hurt his other shoulder fielding fly balls during batting practice. The Senators released him.

“The New York Pennsylvania League president, Vince McNamara, made a decision that I couldn’t play,” Miller said.

Luckily, the Boston Red Sox single-A affiliate, the Oneonta Red Sox, swooped in and signed Miller, allowing him to participate in the all-star game. The series of events led to one of the greatest baseball moments in Miller’s life.

“This one particular day, we’re playing against Batavia. In walks the greatest hitter of all time. There’s a little green fence, a little lower than the Lewes Little League fence, and he walks through with a Ban-Lon shirt on and says come over. Ted Williams proceeded to talk to us for two hours,” Miller said.

Williams, whom Miller called the master of hitting, talked about pitch selection and how he never swung at the first pitch.

“He talked about the sphere, the ball itself, and the fact that the baseball has a top, middle and bottom. He said if you go up there and on that particular day everything you’re hitting is going in the air, it means you’re looking at the middle of the ball, but you’re actually hitting the bottom. Instead of looking at the middle, Williams said, look at the top of the ball next time, so instead of a fly ball it is a line shot,” Miller said.

1966 would be the last year Miller played for a Major League Baseball organization, but it wouldn’t be until the end of August 2023 that Yankee would hang up the cleats for good. His most recent venture, playing for the Lewes Base Ball Club, led to him receiving a special proclamation for a life of baseball from the State of Delaware and Sen. Russ Huxtable, D-Lewes.

While he might not be playing anymore, Miller’s involvement in the Saints Prison Ministry still keeps him connected to the sport he fell in love with as a child.

A lifelong Phillies fan dating back to the 1950 Whiz Kids, Miller is someone who believes in the power of baseball, and the numbers associated with it.

The ministry he works with teaches several sports, mainly softball, to people serving lengthy prison sentences, along with evangelizing. Miller said over 70% of the prisoners he works with are serving life sentences. His greatest joy is the look of hope he sees in inmates' eyes and smiles on their faces when the mission’s message has landed.

Miller’s lucky number is 17, and he holds his high school’s all-time record for season batting average at .517. A home plate in baseball? Seventeen inches. By pure coincidence, his story will be in the Oct. 17 edition of this paper. A baseball life can be full of ups and downs, but Miller believes he came out on the winning side after all.

“It’s kind of interesting that we’re talking like this, because there aren’t too many people that are still alive and have talked to Ted Williams or had instructions from him,” Miller said.

Without the trials of his professional career, there’s a chance Miller would have never learned from the last player to ever hit .400 in a major league season.